The Burma Circle of the Geological Survey of India and their Contributions to the Geology of Myanmar

An Outline of the Tertiary Geology of Burma

This article is the continuation of the previous Episode 43, entitled “An Outline of the Tertiary Geology of Burma”, contributed by Prof L Dudley Stamp in 1922.

The Geography of the Tertiary Period in Burma.

No apology is tendered for attempting to consider the Tertiary geology of Burma from the point of view afforded by a reconstruction of the geography of the period. The reconstruction is based, of course, on detailed study in the field and laboratory, a great part of the information being now available in published form. Despite the lack of knowledge concerning many parts of Burma, this palaeogeographical picture may be considered reasonably correct, and it helps to explain many facts that are otherwise difficult to interpret. More importantly, perhaps, it supplies a simple means of visualizing and memorizing a mass of facts – an advantage not to be ignored in attempting a comprehensive view of the world’s stratigraphy.

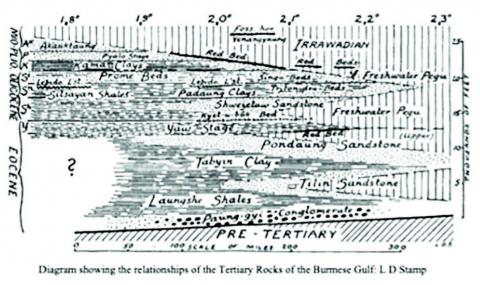

As already pointed out, the main folding of the Shan Plateau, as well as the earlier stages of the uprise of the Arakan Yoma, took place in the pre-Tertiary, probably in late Cretaceous times. There is every reason to believe that the former was a land mass from the earliest Tertiary times and that the latter formed a narrow ridge separating two arms of the sea- the Gulfs of Assam and Burma. The line of the Arakan Yoma continued through the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of Sumatra and Java, but most probably, this line was breached by the sea throughout the Tertiary period, just as it is at the present day. The history of the Tertiary period in Burma is largely that of the infilling of the Burmese Gulf, a great geosyncline that is dominated by sediments, both continental and marine. Flowing into the gulf from the north, one or more rivers poured in huge masses of sediment. The Irrawaddy of the present day may be looked upon as the remnant of this great Tertiary river system.

There has been, generally speaking, a gradual movement southwards of deltaic conditions from the Eocene to the present and a consequent retreat of the sea towards the south. It follows that:

a. the Tertiary succession is predominantly marine in the south and mainly continental in the north,

b. each horizon can be traced laterally from marine through deltaic into fluviatile or aeolian deposits as one goes northwards,

c. there is, on the whole, a tendency for continental conditions to move southwards as one ascends in the succession. The continental type of Pliocene (Irrawadian) is the most widely spread of all the continental deposits.

Certain other important factors must, however, be considered. Throughout the Tertiary period, there seem to have been movements of folding and uplift along the line of the Arakan Yomas, culminating in the great folding movements that affect all the Tertiary deposits of Burma and which took place towards the end of the Pliocene. It is not possible to point to any great unconformities amongst the Tertiary strata of Burma, though much has been written on their occurrence or otherwise. The observed cases fall into two groups: -

a. “ravinements” such as occur almost invariably at the base of Cycles of sedimentation. Examples: the base of the Yaw Stage in the Lower Chindwin District, and probably also the base of the Irrawaddy in the Oilfields of Minbu, Yenengyaung, etc. The intra-formational “unconformities” frequently observed in the Pegu System belong to this class,

b. local unconformities due to the denudation of the minor folds produced as a result of the “buckling” of the floor of the geosyncline during the Tertiary period. A good example is seen in the Myaing region, where the Irrawadian rests directly on the Pondaung Sandstone.

An extreme case, and one of great interest, of the effect of the minor folding in the floor of the geosyncline is seen around Shinmadaung near Pakokku. Here, in the very midst of the Tertiary Belt, a ridge of the pre-Cambrian gneisses, which must form the floor of the old gulf, appears at the surface as a result of folding and faulting. The exact relationship with the surrounding Pegu rocks is uncertain, but the lowest Pegu (Shwezetaw Sandstones) appear to rest directly on the gneiss. It may be noted that this locality is along the line of Tertiary volcanoes, which pass through the midst of the Tertiary Belt. Around Shinmadaung, igneous rocks are found interbedded with Pegu and probably with Irrawadian sediments.

The Tertiary Succession and its Classification

The Tertiary succession in Lower Burma is very different from that in Upper Burma. A failure to recognize the importance of lateral variation and the wedging out of marine beds when followed northwards has caused considerable confusion and invalidates much that has been written on the Tertiary geology of Burma. The progress that has been made in this respect within the last few years is largely due to the work of Dr G de P Cotter.

It may be said at once-

a. that very little is known of the succession in the Sittang Valley, that Is to say, on the eastern side of the Pegu Yoma,

b. that the Eocene strata are very imperfectly known,

c. that may point to the correlation of the succession in Upper and Lower Burma, which is still uncertain. It is found, however, that most of the principles of the cycle of sedimentation can be applied on a large scale to the interpretation of the Burmese sequence. An attempt diagram also indicates roughly the lithology of the beds. Under “continental” are included aeolian, lacustrine, fluviatile, and some brackish water deposits.

Eocene

1. Southern Region (Nicobar and Andaman Islands and Lower Burma) In the Andaman Islands, the Eocene is represented by a series of conglomerates and sandstones resting unconformably on and containing pebbles derived from the underlying rocks, which are probably Cretaceous and comparable with the Axial Group of the Arakan Yoma. In passing, it may be noted that the deepest water in Eocene times lay to the south, and the deposits of this age are represented by limestones in parts of Sumatra and Java. Little is known of the Eocene rocks of Lower Burma (Henzada and Prome Districts). They consist mainly of unfossiliferous shales and sandstones that are much disturbed by faulting. The junction with the pre-Tertiary rocks appears to be invariably faulted.

1. Northern Region (Upper Burma) Here, the Eocene rocks are of greater interest and have been studied in some detail, especially regarding the higher beds. The succession is: -

5. Yaw Stage (marine shales).

4. Pondaung Sandstones.

3. Tabyin Clays.

2. Tilin Sandstone.

1. Laungshe Shales with Paung-gyi Conglomerate at or near the base.

Paung-gyi or Swelegyin Conglomerate: A typical basal conglomerate from 2,000 to 4,000 feet thick. The contrast between the folded but comparatively unaltered conglomerate and the underlying cleaved and folded shales or phyllites (Kanpetlet Schists, etc.) has already been noted. The pebbles in the conglomerate seem to consist of fragments of these rocks together with a few gneisses of a more distant origin.

Laungshe Shales: Possibly from 9,000 to 12,000 feet in thickness. The fauna of these beds has not yet been studied, but it seems to include several forms of late Cretaceous aspect, possibly survival in the early Eocene gulf. The most abundant fossil is a large Operculina.

Tinlin Sandstone: It is possible that this arenaceous group, marine in the south, becomes brackish or freshwater northwards. It is certainly much thinner in the south and cannot be traced as a separate division to the south of latitude 20°15’. This attenuation from an estimated thickness of up to 5,000 feet in the north to nothing in the south probably accounts for the huge thickness claimed for the Laungshe Shales in the south.

Tabyin Clays: A group of greenish, somewhat rubbly shales up to 5,000 feet in thickness. The most interesting fossil is Nummulites verdenburgi Prever. In the south, other nummulites, some large in size, are found, apparently at this horizon or slightly higher (Minbu district). North of latitude 21°45’the the writer did not succeed in finding any nummulites or other marine fossils, but numerous thin seams of coal occur in the higher part. The coals of Upper Chindwin appear to belong to this and to succeeding divisions.

Pondaung Sandstone: A very interesting series of deposits. The lower part comprises beds of greenish sandstone (weathering yellow), with bands of conglomerate and greenish shale and passes down quite gradually into the Tabyin Clays below (1 in. map, sheet 84 K/5). Fossils here (latitude 21° 50’ to 22° 45’) are scarce but include Arca, Cardita, and other marine forms. Going upwards in the series, the Pondaung Sandstones exhibit a gradual change from marine to brackish and finally to freshwater and land conditions. Plant remains (wood) occur throughout; in the lower part of the wood, it is carbonized, higher up, partly carbonized and partly silicified, whilst in the highest part, it is always silicified. It should be mentioned that silicified wood is highly characteristic of the continental depos its in Burma. As one passes northwards (as from latitude 21° 45’ to 23° 30’), the upper continental beds thicken at the expense of the lower marine. The most striking members of the continental facies are beds of clay- purplish, pale greenish, or mottled – with abundant vertebrate remains indicating their formation in freshwater lagoons. The remains include mammals (Anthracotherium, Anthracohyus, Metamynodon? etc.), crocodiles (Crocodilus), and huge turtles. From about latitude 22° 0’to 22° 30’the highest bed is a “Red Bed” or layer of laterite denoting terrestrial conditions. To the south, the whole of the Pondaung Sandstones become more marine, the mottled or purplish clays are not found much to the south of latitude 20° 30’, and oysters (Alectryonia noetlingi) are here abundant. Large nummulites are common from 20° 5’ southwards. The group is as thick as 6,500 feet in latitude 22° 5’.

Yaw Stage: A series of shaley clays with an interesting fauna, which has been described in part. The series is essentially a marine one, and fossils include Nummulites yawensis Cotter and Velates orientalis Verd. – the latter, especially in the upper part- large Ampullinae, etc. The stage typically develops at about latitude 21( 30’longitude 94( 20’E.; northwards, marine fossils gradually become scarcer and stunted, and the deposit wedges out, being absent at latitude 22° 45’. Owing probably to the proximity of the western shoreline, the deposits are very sandy about latitude 21° 5’, but again become of deeper-water type in the Ngape’-Yenanma area (latitude 19° 50’ to 20° 5’). Eastwards in the Myaing district (latitude 21° 37’, longitude 94° 52’), the series is again of shallow-water type, possibly due to the nearness of the ridge of ancient rocks of Shinmadaung mentioned above. In the north, the base of the Yaw Stage is marked by interesting bone beds, whilst conglomeratic bands with fish remains occur throughout. Concerning the upper limit, northwards from 21° 45’the series passes up gradually into the overlying “ Freshwater Pegu”; whilst in the south, it would appear to be well defined by a bed which the writer prefers to regard as the base of the Pegu. The latter bed, described below, has been traced at intervals for 100 miles, though it should be mentioned in fairness that general agreement as to the identity of the bed throughout has not yet been reached. (To be continued). References:

Stamp, L Dudley. 1922: An Outline of the Tertiary Geology of Burma, the Geological Magazine, Vol LIX.

#TheGlobalNewlightOfMyanmar